LISTEN

Racism has been built into every facet of our daily lives, from government to education; it is systemic and institutionalized.

One of the best ways to learn about racism is to listen to the people whom it affects most acutely: BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color) individuals.

Those of us who have the privilege to have never experienced racism or discrimination must listen with compassion and love—and believe those who choose to share their stories.

And Jesus said to them, “Pay attention to what you hear; the measure you give will be the measure you get, and still more will be given you.

— Mark 4:24

Lord, make us instruments of your peace. Where there is hatred, let us sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is discord, union; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where there is sadness, joy. Grant that we may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; to be understood as to understand to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life. Amen.

—A Prayer attributed to St. Francis, Book of Common Prayer, p. 833

SYSTEMIC RACISM

Systemic racism explains the way that racism has been built into our daily lives. It is the overall system of oppression designed to disenfranchise people of color. It includes structural and institutional racism which are the legal pathways and institutional rules which seek to uphold discrimination. It affects every facet of life, from housing to healthcare, education to law enforcement, and wages to accruement of generational wealth.

In defining types of racism, The Aspen Institute explains that structural and systemic racism are nearly synonymous, with the exception that structural racism concentrates on “the historical, cultural and social psychological aspects of our currently racialized society.” The Aspen Institute describes systemic/structural racism as, “a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity. It identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with ‘whiteness’ and disadvantages associated with ‘color’ to endure and adapt over time. Structural racism is not something that a few people or institutions choose to practice. Instead it has been a feature of the social, economic and political systems in which we all exist.”

Click here to view the Glossary for Understanding the Dismantling Structural Racism/Promoting Racial Equity Analysis prepared by The Aspen Institute

The video on the left outlines the differences between structural, institutional, and systemic racism and how they affect people of color in the United States.

This video was part of a news report on ABC7 in San Francisco. Video provided courtesy of YouTube.

ROOTS OF SYSTEMIC RACISM

According the Black Americans and the Law, published by Berkeley Law School, “American jurisprudence and law have profoundly shaped, defined, and constrained the lives of Black people for over 400 years. Racial inequality has extremely deep roots in American society, and our Constitution, statutes, court cases, and regulations not only bear witness to this, but are often the source of it.”

Click here to view the Berkeley Law School timeline that highlights the most important court cases and legal actions that helped create our current legal system of oppression.

THE RISE OF JIM CROW & ANTI-BLACKNESS

Following the abolition of slavery after the Civil War, the United States entered a period of Reconstruction (1865-1877) where the Union attempted to reintegrate mutinous southern states from the Confederacy.

The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were passed—which abolished slavery and attempted to guarantee equal protections under the law for all Black people, including the formerly enslaved. Black men were voted into office across the country, including in the South.

During Reconstruction, “16 African Americans served in the U.S. Congress during Reconstruction; more than 600 more were elected to the state legislatures, and hundreds more held local offices across the South” (History). Reconstruction also witnessed the birth of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization founded by a Confederate general to restrict the freedoms and social equality of the formerly enslaved. The Equal Justice Initiative has curated articles and short films illustrating the strides towards equality for Black Americans during the Reconstruction Era, as well as the beginning of organized violence and racial terror against them.

The KKK was filled with former Confederate leaders, soldiers, and family members who actively sought to reframe history, while terrorizing Black people across the country. They helped to perpetuate the idea of the Lost Cause with the Daughters of the Confederacy, and worked to keep white supremacy embedded in the culture of this country. This group normalized lynchings, massacres, and parades to demonstrate their legitimacy and terrorize Black people and their allies.

It is important to remember that while the roots of systemic racism begin with the chattel enslavement of Black people in the Americas, it was fed by white supremacist thinking, the ideal of “whiteness,” the legal racial and cultural apartheid created by Jim Crow segregation, and the terrorizing of Black people by white supremacist organizations through violence.

EFFECTS OF SYSTEMIC RACISM

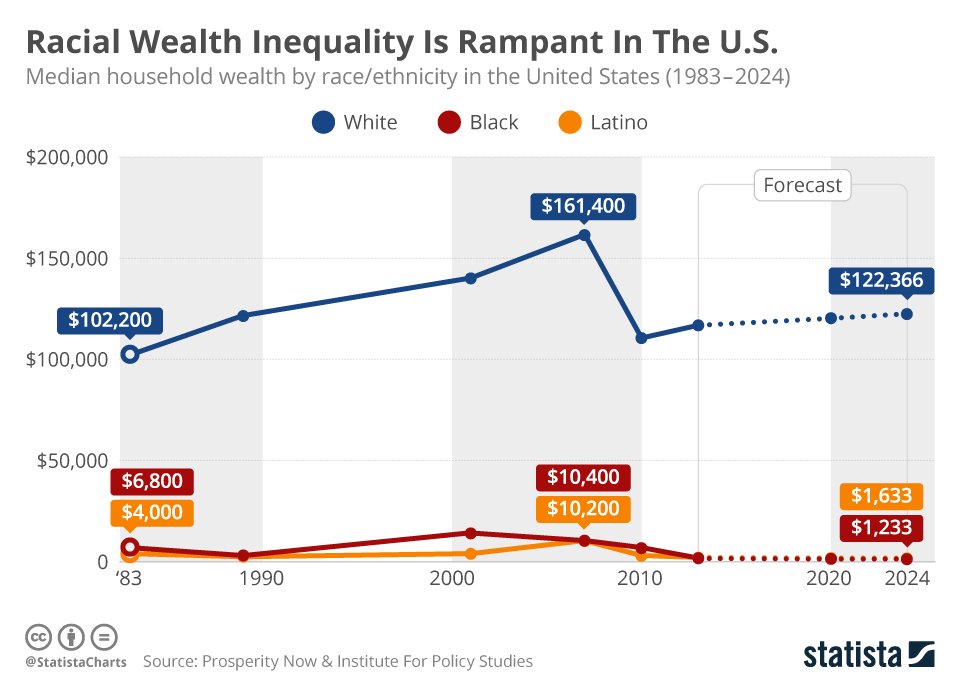

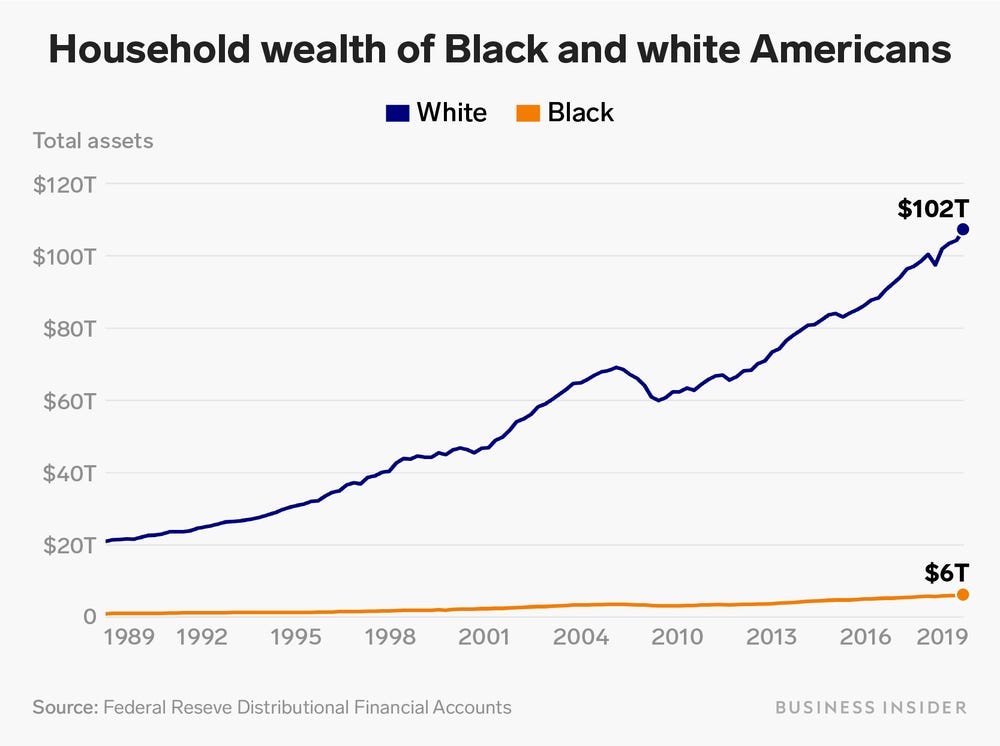

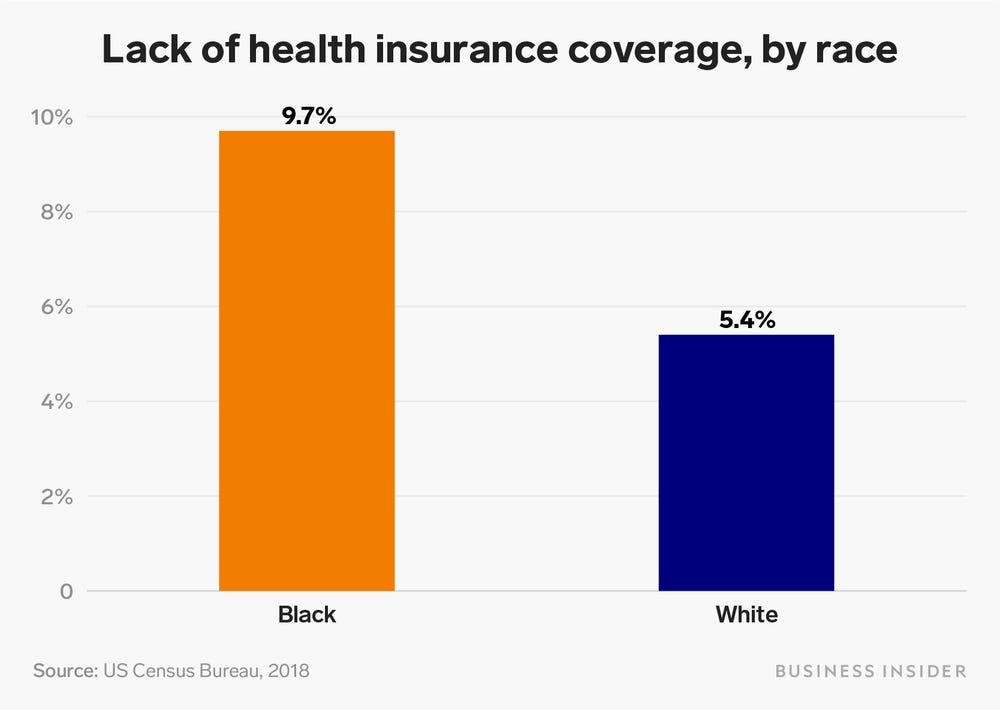

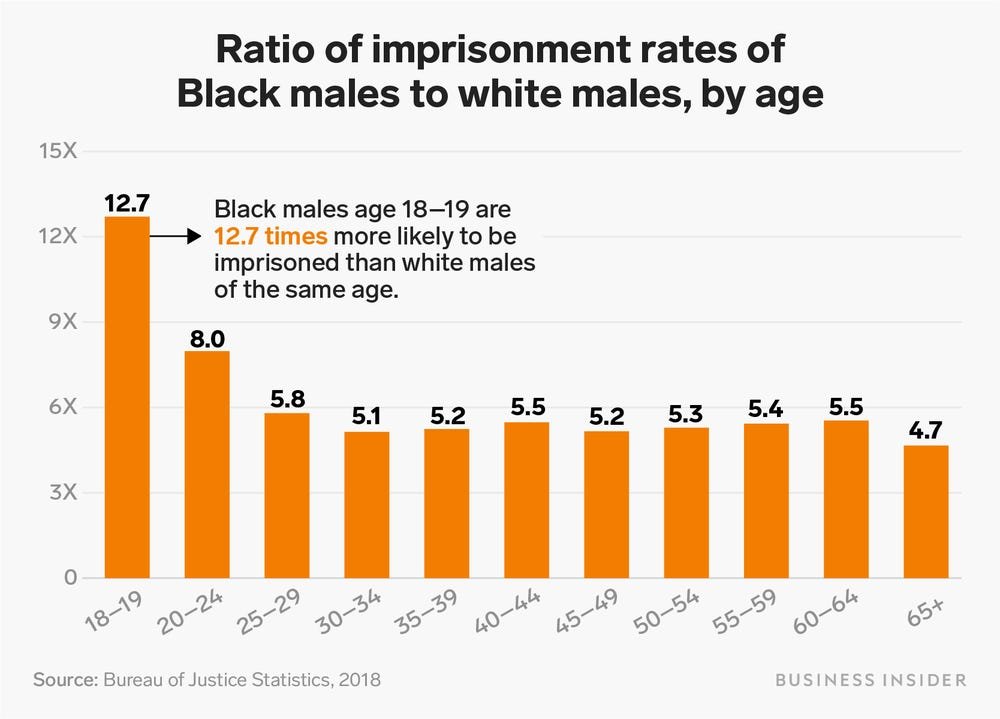

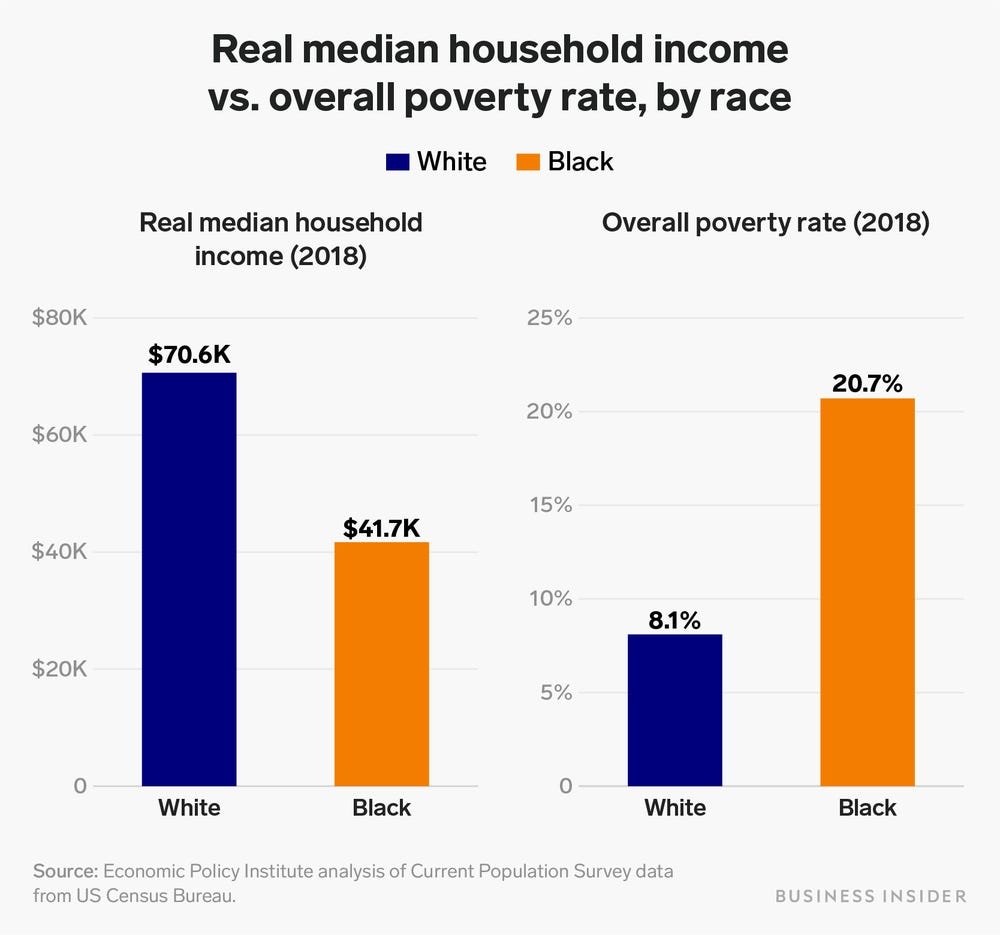

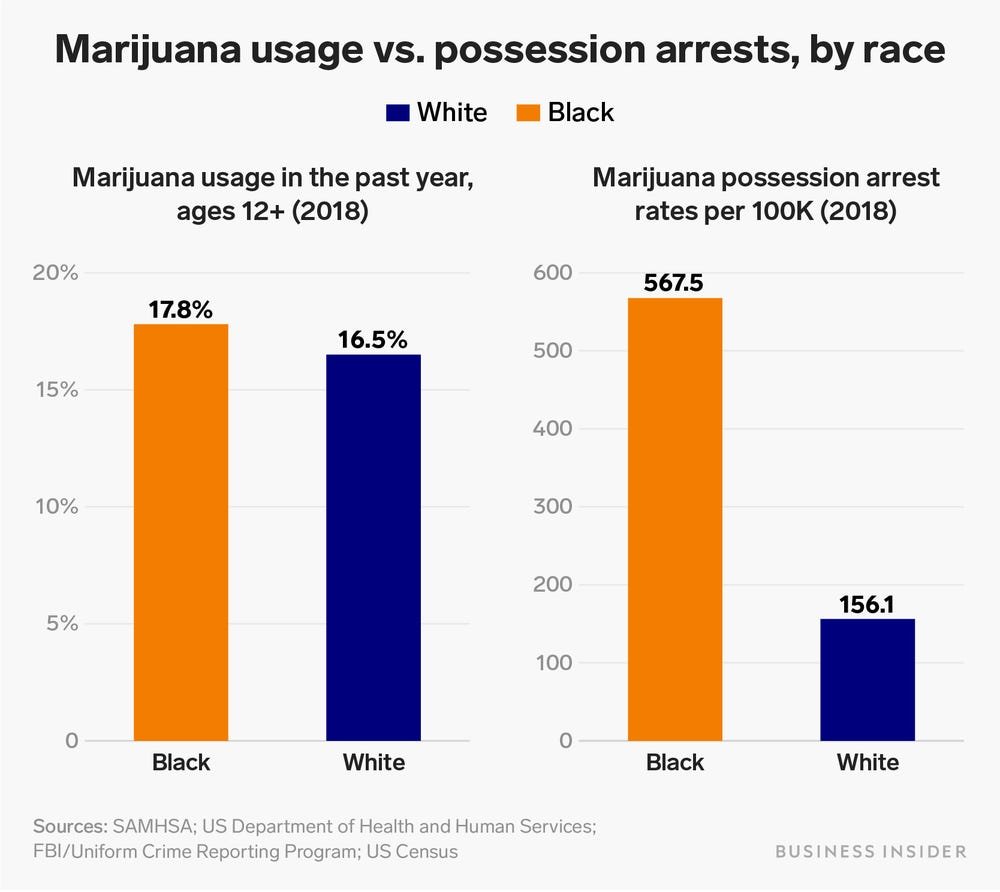

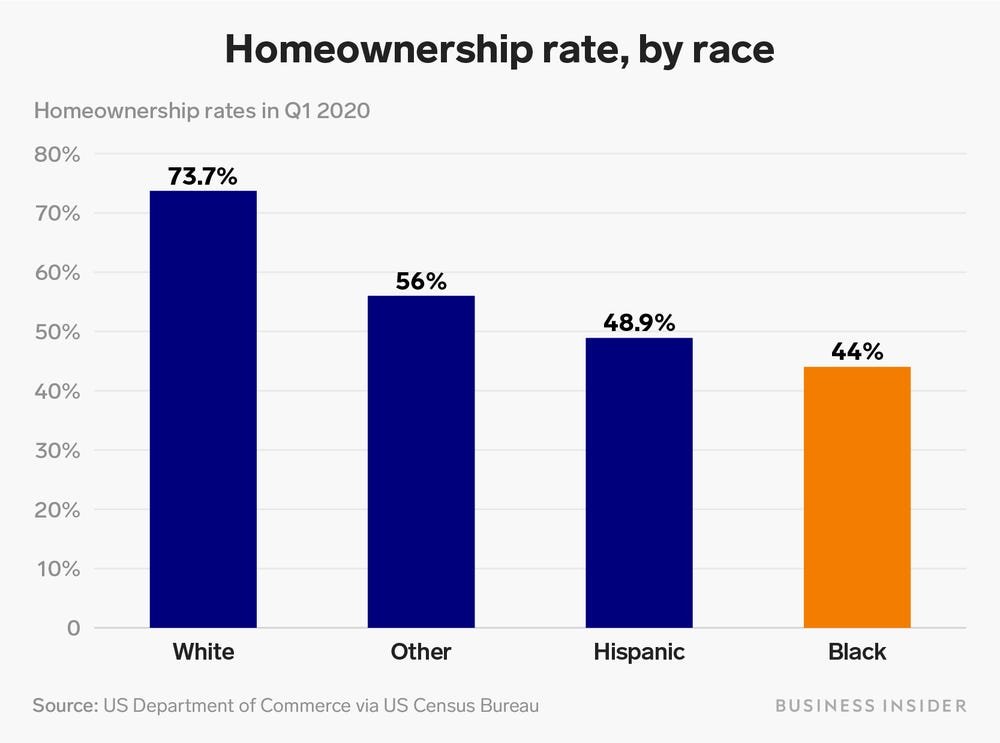

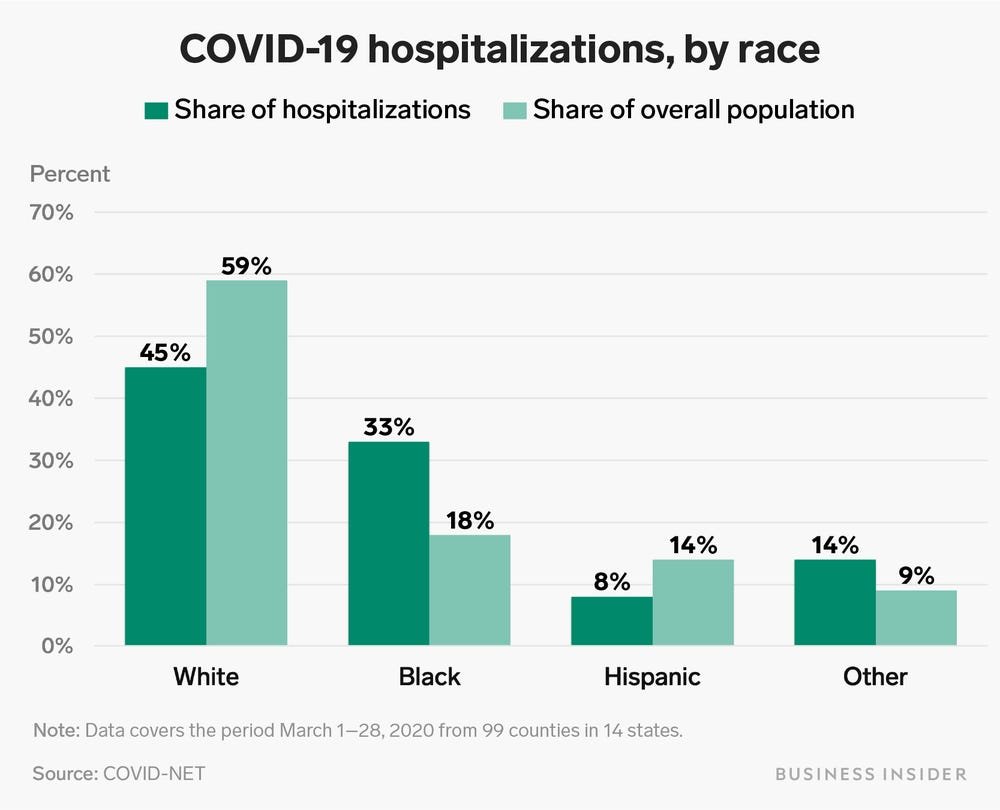

Systemic and institutional racism is readily apparent in hard data. According to Reuters, “inequality between white and Black Americans persists in almost every aspect of society and the economy. Such disadvantages have proven immune to decades of laws and policies meant to address them, leaving Black people with less education, less wealth, poorer health and shorter lifespans…wide gaps—rooted in the legacy of slavery, segregation and discrimination—have endured or widened in the years since the civil rights victories of the 1960s. Born from the enslavement of Africans in British colonies since the early 1600s, American inequality plays out over the course of a lifetime.”

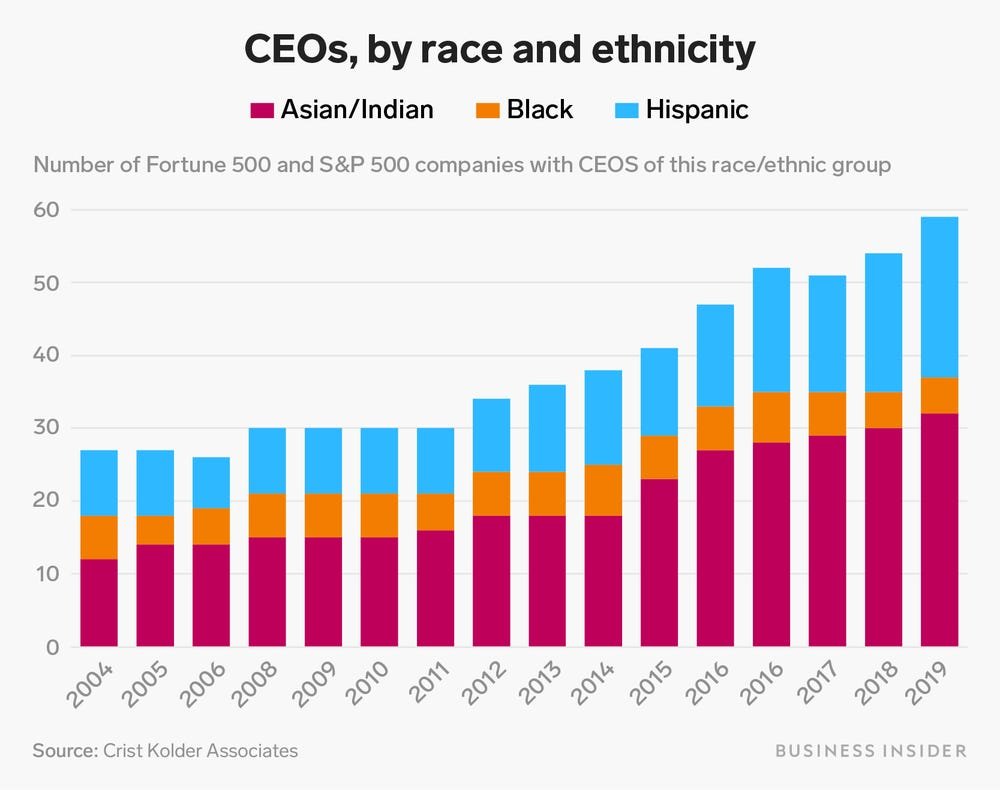

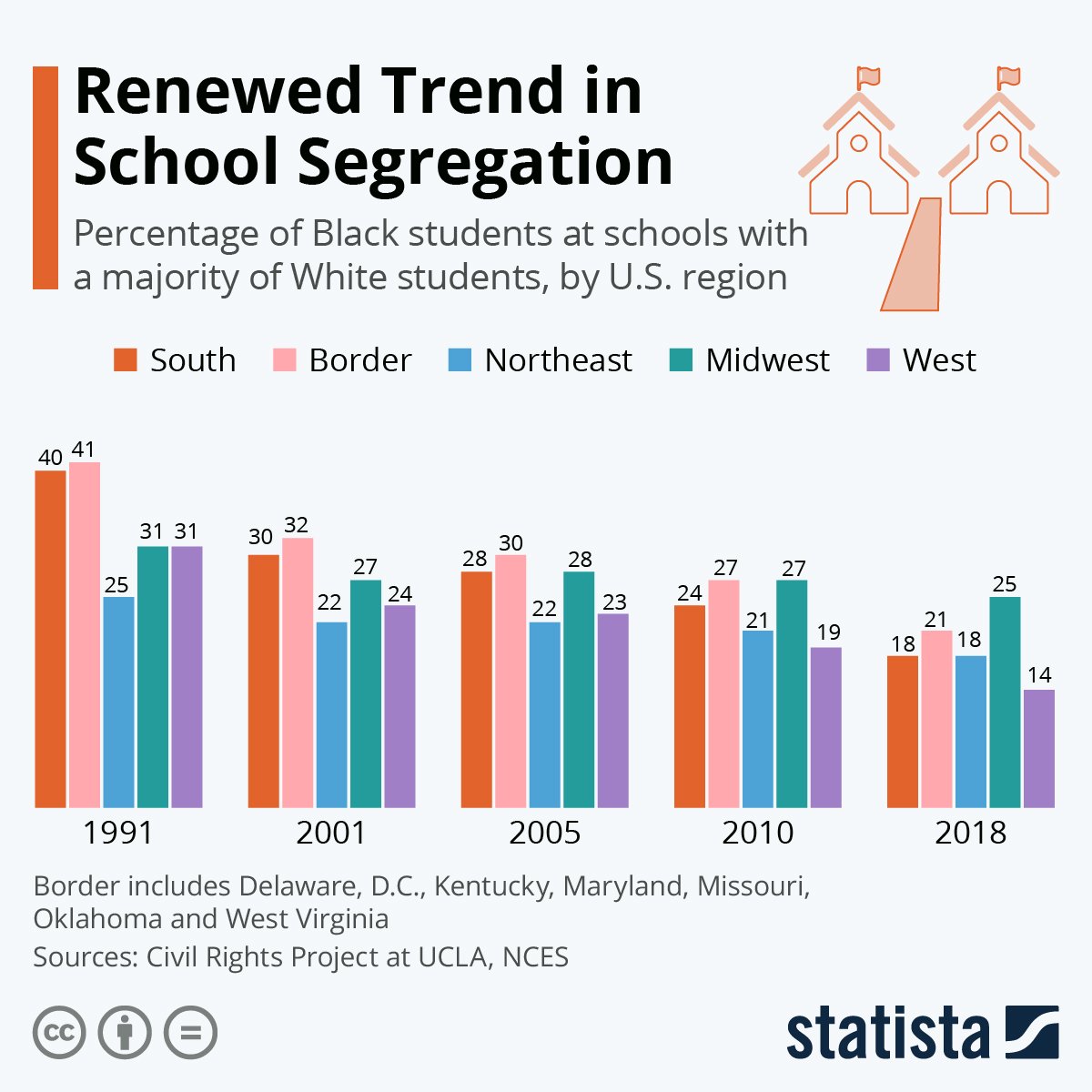

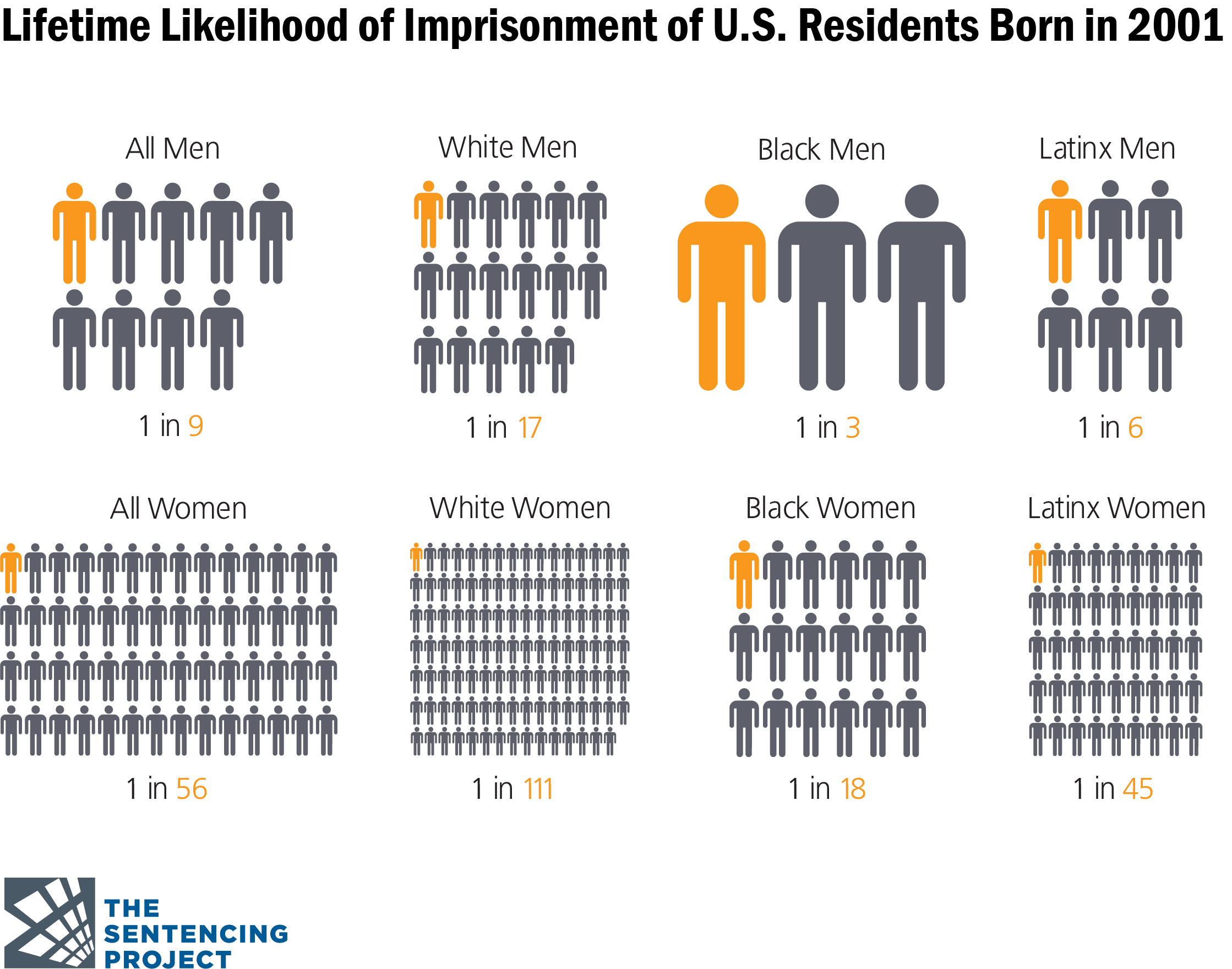

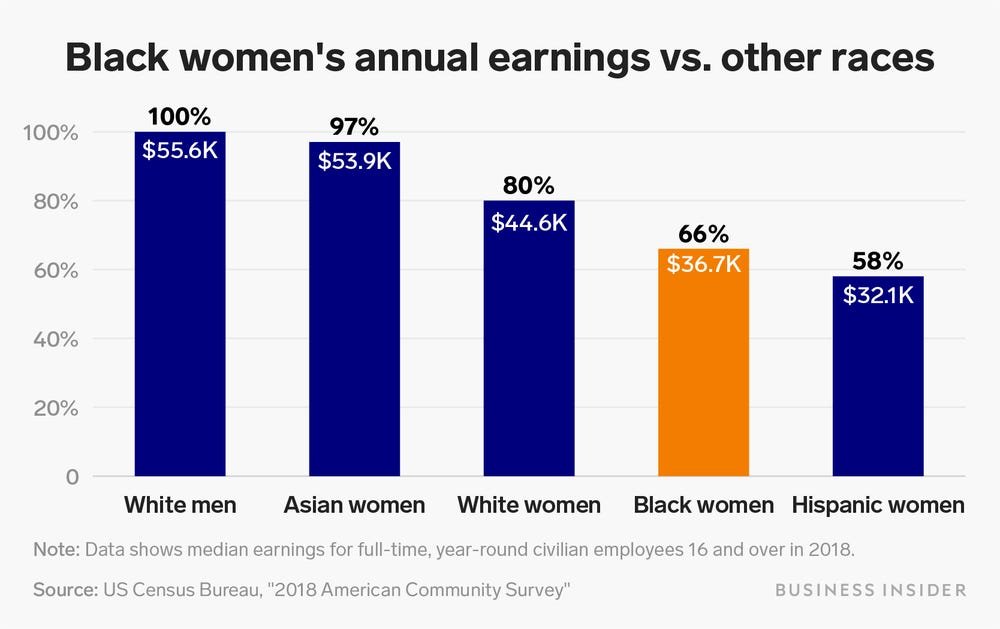

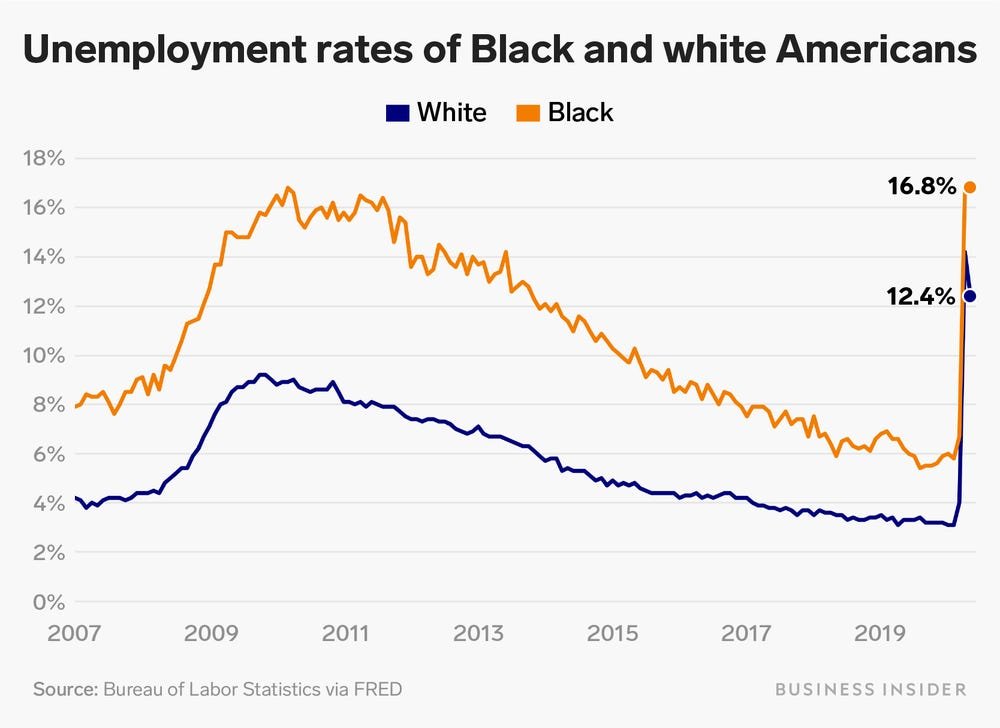

Review the charts and graphs below to see a snapshot of some of the challenges faced by BIPOC populations in the United States.

In July 2020, Reuters published a report outlining the effects of systemic disadvantages rooted in codified racism and bias affecting Black people in America. Click below to view The Black White Gap.

Let me not look away, O God, from any truth I should see. Even if it is difficult, let me face the reality in which I live. I do not want to live inside a cosseted dream, imagining I am the one who is always right, or believing only what I want to hear. Help me to see the world through other eyes, to listen to voices distant and different, to educate myself to the feelings of those with whom I think I have nothing in common. Break the shell of my indifference. Draw me out of my prejudices and show my your wide variety. Let me not look away.

—The Right Reverend Steven Charleston, Choctaw

ACTIVITY | EXAMINING PRIVILEGE

In 1989, then Associate Director of the Wellesley College Center for Research on Women, Peggy McIntosh published an article titled, White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, in which she outlined the advantages all white people experienced as a result of systemic racism. In it, she listed 26 ways in which the color of her skin made her life easier.

View the video to the right of Dr. Susan Borrego, Chancellor of the University of Michigan-Flint. Her TEDx talk examines the realities of white privilege and what it means for our society.

Meditate on the ways in which your life has been helped by your own privilege. Privilege is not one dimensional. Privilege is intersectional in that it is shaped by not just race, but ethnicity, gender, physical ability and a host of other categories. While systemic racism operates to oppress unilaterally, our experiences are individual and specific to our experiences.

Read Peggy McIntosh’s list of examples of her privilege as a white heterosexual woman in America. Make a list of examples of your privilege. This can and should include privileges conferred by your race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, religion, language, sexuality, physical ability, family support (in regards to neighborhood, housing, education, and generational wealth).

From your list, does it seem that you are a product of systemic privilege? That is, do you benefit from systemic discrimination? If so, how?

Make a list of the ways in which you have been disenfranchised from systems of power. Which has happened to you more frequently, benefitting or disenfranchisement?

SYSTEMIC RACISM IN HOUSING

Inequities in housing are a direct result of systemic racism. In 1934, President Roosevelt enacted the Fair Housing Act to provide home buying aid through loans and mortgages. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which was created through this Act, provided federal backing to home loans. Loan availability was determined using a manual from the government backed Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) which graded and color coded real estate areas. Overall, neighborhoods populated by Black and immigrant populations were coded Grade D, Hazardous, and colored in red. Individuals that lived in areas that were outlined in red were predicted to be more likely to default on loans. This gave rise to the term redlining.

According to the Federal Reserve, redlining is the practice of denying a creditworthy applicant a loan for housing in a certain neighbor hood even though the applicant may otherwise be eligible for the loan. The term refers to the presumed practice of mortgage lenders of drawing red lines around portions of a map to indicate areas or neighborhoods in which they do not want to make loans (Federal Reserve).

EXPERIENCE | REDLINING & MODERN SEGREGATION

What is redlining and how did it affect BIPOC Americans? Watch the NPR video to the left for an examination of the origins of redlining and the effects it has had on generations of Americans of color.

The American Panorama Project is “an historical atlas of the United States for the twenty-first century” which uses interactive mapping and historical data to illustrate periods and initiatives in US history. Click below to visit Mapping Inequality, an interactive map that shows HOLC grading between 1935 and 1940.

Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers

As a part of The Roots of Structural Racism Project, The Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley has created an interactive map that provides historical context and records as well as a modern look at housing segregation in America. Click the button below to look at New York City and Long Island and review the data for your neighborhood.

HOUSING DISCRIMINATION HAPPENS WHERE YOU LIVE

While systemic racism and housing discrimination seem far removed from the boroughs of New York City and Long Island, it is a huge problem for our area. The roots of bigotry and racism run deep.

Thanks in part to the diversity of Queens county (it is the most ethnically and linguistically diverse county in the US [Axios]), New York City and Long Island benefit from being one of the most diverse cities in the country, however, it is one of the most segregated. According to a 2019 investigative project by New York Newsday, “there are 291 communities on Long Island, and most of its black residents live in just 11.” Click the button to view the 3 year investigative report uncovering widespread discrimination on Long Island.

In June 2019, clips of a 1976 documentary film by Bill Moyers were tweeted. The clips showed a group of all white residents of Rosedale, Queens harassing young Black children who had unwittingly stumbled upon their anti-Black demonstration. The film, “Rosedale: The Way It Is” showed racial tensions in the white working-class neighborhood when a Black middle-class family moves in. The tweet prompted an investigative piece by the New York Times following up on the white demonstrators and the Black children in the documentary film. Click the button below to learn more and to watch Rosedale: The Way It Is.

Learn more about Redlining and Housing Segregation within the Diocese

ACTIVITY | DO JUSTICE. LOVE KINDNESS. WALK HUMBLY.

The Diocese of Long Island has partnered with FaithX to create a set of interactive maps that reveal the presence and power of systemic racism within Brooklyn, Queens, and on Long Island.

Spend some time exploring the maps for your neighborhood and throughout the Diocese. The entirety of Long Island has been mapped to illustrate the effects of institutional racism within our communities.

What is your race and ethnicity? What is the primary race in your neighborhood?

What is your access to supermarkets, highly rated healthcare, parks and green spaces, good schools, reliable utility services, and city services like police and fire stations?

How does that differ from other communities nearby?How do the FaithX maps illustrate the effect of systemic racism on your daily life?

If your parish has partnered with another church or churches as part of Indaba or a discussion project, look at the location of their parish and compare your neighborhoods.

a. What is the primary ethnicity of your partner church? How does that compare with your parish?

b. Look with compassion at their neighborhood’s history and discuss the effects of systemic racism within their community as a window into understanding its effects on their lives.

Click here to participate in Do justice. Love kindness. Walk humbly.

EXPERIENCE | STORYSHARING

In the Fall of 2020, the Episcopal Diocese of Long Island, hosted part of the Beloved Community StoryMaking team on the Presiding Bishop’s Staff. Churches use this community building process to deepen their love for one another and enrich their common mission and understanding of one another and the gifts of life they bring to the parish. The process of sharing stories can be used in multiple ways within parishes, as a small group event, or as part of an Indaba, Dialogue Circle or community activity between parishes telling stories, in the variety of ways offered in the StorySharing program.

Beloved Community Storysharing webinar was offered in December of 2020 with Ellis Reyes Montes, Sandy Millien, and Isaiah Shaneequa Brokenleg.

Click here for the StorySharing Guide for Small Groups

Participants from All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Park Slope reflect on their experience with StorySharing